South Africa is a country rich in culture and language. It enjoys a diversity of groups who all have unique and intricate indigenous music sounds. Because of its wide-ranging genres, its folk music is often exported under the umbrella “world music” term. Unfortunately, this barely casts light on the nuances and history that make each sound distinct and exceptional.

It would take several book volumes to cover the entire scope of music that has sprung from all the regions of this beautiful country, so here we take a look at some of the more popular styles and the iconic artists who shaped and evolved the sound.

Zulu

Maskandi

The traditional music most associated with the Zulu nation is maskandi, a genre pioneered by migrant workers living in hostels and compounds (enkomponi) near mines in the 1960s. The music, which was typically played on guitar, conveyed a melancholic yearning for home and a desire for a better life. Originally the domain of men, female artists, such as the late Busi Mhlongo, have also made their mark.

Picture credit: Leon Morris (Getty Images)

“Maskandi” is a derivative of the Afrikaans word “musikant” and uses vernacular lyrics – with instruments such as guitar, concertina, violin and piano accordion – to create a distinct high-pitched sound. Maskandi artists often begin a song with poetic traditional praises; as can be seen in this below clip, featuring one of the most popular Maskandi acts, Ihashi Elimhlophe (sometimes styled Ihhashi or Ihha’shi Elimhlophe).

Over the years Maskandi has evolved and been incorporated into more mainstream music styles. However, it still has nostalgic appeal and remains one of the most poetic and evocative styles to come out of marginalised communities.

Mbaqanga

Mbaqanga is another indigenous music style which sprang from the Zulu culture. Due to its use of Western instrumentation and indigenous vocal stylings, it is widely considered a form of jazz. It developed in South African shebeens in the 1960s out of Marabi (a style of township music) and Kwela (pennywhistle-based street music) and evolved to include heavy elements of American big band swing.

Artists such as Miriam Makeba (famously known as Mama Africa), Dolly Rathebe and Letta Mbuli popularised the style and helped export it to international markets in the 60s and 70s.

Isicathamiya

Isicathamiya is a type of acapella music, closely related to gospel, made famous by Ladysmith Black Mambazo (featured below). It is identifiable through its use of multiple voices and harmonies to create a single voice. Isicathamiya choirs are made up mostly of basses, a few tenors, alto and a lead voice. The sound heavily emphasises the bass voices

In the early 20th century, Zulu migrant workers travelled from rural areas to urban areas to work in South Africa’s mines. These migrant workers entertained themselves during these long periods away from home through song and dance. Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s distinct movement style is a remnant of that time. In his biography, leader Joseph Shabalala details how the “tip toe” style was designed so as to not disturb the security guards at the migrant worker’s camp. When miners returned to the homelands, they took the style and movement back with them.

Xhosa

Photo credit: XhosaCulture.co.za

The amaXhosa nation has a rich history of musical expression rooted in their oral tradition. Made up of subgroups such as amaThembu, amaMpondo, amaBhaca and amaFengu, they are a proud and diverse group of clans who each have distinct cultural practices that heavily influence their sound.

Madosini Manqina (also known as Latozi Mpahleni) is considered the queen of Xhosa folk music. The composer and instrumentalist is undeniably one of the most influential figures in indigenous sound.

Born in 1945 in Mqhekezweni (Libode), a village in Mpondoland in the Eastern Cape, she began playing various instruments as a child through instruction from her mother. Because of illness, she spent a lot of her early years making and playing instruments and by age 13 she was entertaining local villagers.

Not only is she a legendary storyteller, she plays and makes Uhadi (berimbau), Isitolotplo (Jews’ harp), Umrhubhe (mouthbow) and has a unique ability to invoke wonder through mysticism.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pyPQ9dXN9ck

AmaXhosa make up a huge percentage of popular folk music artists on the South African music scene today. From Thandiswa Mazwai’s stirring and experimental take on ethnic rhythms and Simphiwe Dana, whose sound is more jazzy and sombre, and the Afropop stylings of Nathi, Amanda Black and Vusi Nova, they are a nation whose artistry keeps evolving.

Photo credit: Michael Loccisano/Getty Images

Basotho, Batswana, Bapedi

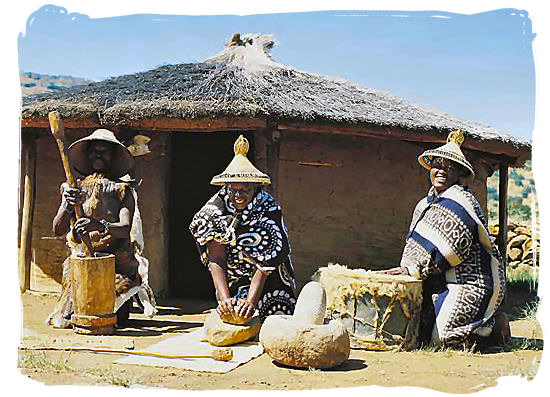

Picture credit : South African Tourism

Famo

In Lesotho the genre known as Famo – a combination of storytelling, accordion and oil-can drum – was born. With its origins in initiation ceremonies and other traditional celebrations, it was the foundation for many styles to come. Uhuru, later known as Sankomota, is one of the earliest music success stories to come out of this mountainous Kingdom.

Famo originated from drinking holes frequented by migrant workers from Lesotho who were working in South African mines in the 1920s. It grew from the setolotolo (bow songs) which were sung by men and evolved to include European instruments.

Picture credit: musicinafrica.net

Famo was the foundation for many styles to come. The legendary band Sankomota, formerly Uhuru, evolved the sound by merging its rhythmic elements with jazz and rock. Formed in 1976, Sankomota consisted of several members (including breakout star Tšepo Tšola) and their hit song “Stop War” (below) is a great example of the evolution of Famo to incorporate Jazz instrumentation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uBY_SCyajOQ

Motswako

Like many others, the Batswana ethnic group is divided into a number of subgroups scattered along various regions, from the Okavango River in the northwest, to the upper parts of the Limpopo, the Kuruman area and the northeast of the Orange River in Botswana and Namibia. In South Africa, the Batswana are in the north.

The Batswana nation gave the world Motswako, a genre of hip hop popularised by artists such as HHP and Khuli Chana. Motswako artists rap in their native Tswana, English and other languages over hard-hitting beats that sample traditional sounds. Recently, artists from this movement have crossed over to the mainstream, with great success. Below is Khuli Chana’s Cannes Lion-winning (gold, two silvers and bronze in the Entertainment, Entertainment for Music and Media categories) video for “One Source”.

Cassper Nyovest (real name Refiloe Maele Phoolo) is arguably the most mainstream product of Motswako and one of the most successful local acts in recent years – last year he sold a record-breaking 68 000 tickets for his showing at FNB stadium, a first for a local hip hop artist.

Photo credit: Cassper Nyovest

Kiba

The Bapedi people in the Northern parts of South Africa – sometimes referred to as Northern Sothos, though this is considered a colonial classification – are known for music with a heavy use of flutes and a plucked instrument called dipela. Later instruments such as the Jew’s harp and the German autoharp became in use to make music known as harepa. Their most popular genres are Kiba – which is typically made by a group of men playing dinaka (open-ended flutes) – and kosa ya dikhuru (knee-dance music) which is characterised by chanting and a kneeling dance. Percussionist and activist Sello Gallane, known for his song, Pula, is probably the most well-known Kiba musician.

Picture credit: Boksburg Adviser

Ndebele

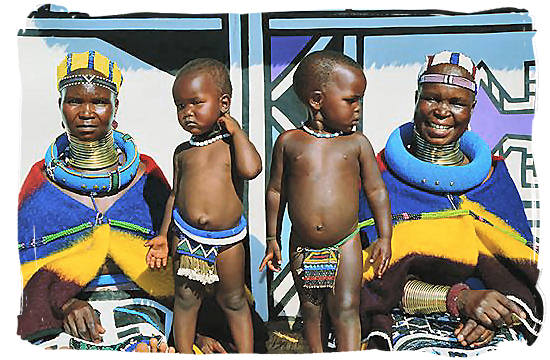

Picture credit: South African Tourism

The Ndebele nation in South Africa consists of two distinct – and culturally diverse – groups. In the Northern Province they are made up mainly of the BagaLanga and BagaSeleka groups who over the years have been influenced by their Sotho neighbours in terms of language and culture. The Ndzundza Ndebeles of Mpumalanga and Gauteng are probably the most distinguishable through their famous house-painting, beadwork and decorations. They speak the only variation of the language that is written, which is closely related to the Zulu language.

The traditional music of amaNdebele is also diverse, with choral elements accompanied by leg rattles (amahlwayi), clappers (izikeyi) and instruments such as the mouth bow, isighubu (drums) and isiginxi (guitar).

Picture credit: Getty Images

Peki Emmelinah “Nothembi” Mkhwebane is the legend of indegenous Ndebele music. Born in Carolina in Mpumalanga, South Africa in 1953, she grew up ploughing fields and looking after cattle and was taught to play instruments like isikumero, isidonodono and the african drum (iingubhe) by her grandmother during lunch breaks. Her uncle also taught her to play a home made oil tin guitar.

Picture credit: Pan African Space Station

Nowadays she also uses the keyboard and acoustic and electric guitar to make her award-winning compositions. She sings in a distinct high-pitched voice to deliver melancholic Ndebele lyrics about the state of society and is a dynamic performer as seen in this clip.

XiTsonga

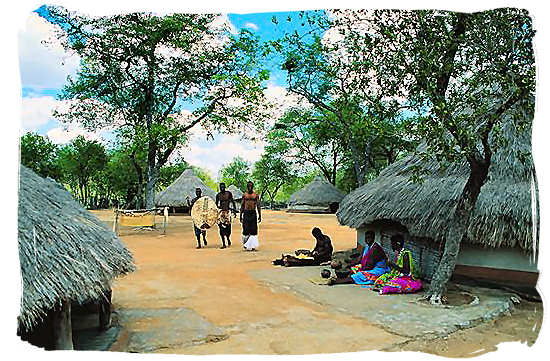

Photo credit: South African Tourism

Historically, Tsonga people migrated from the Northern parts of South Africa to what was then known as Transvaal in the 18th century. During the period of warfare known as Mfecane, King Shaka ordered general Soshangane to conquer them. Terms Shangaan and Tsonga thus became interchangeable – this is now politically incorrect as not all Vatsonga are “Amashangane”.

Credit by: Kaross

The Vatsonga traditionally use instruments such as xipendana, mqangala, xitende and xizambi (mouth bows) and the xitiringo (flute) and mohambi (xylophone) and numerous others in ritual ceremonies.

Though there are many Xitsonga artists and superstars (including ‘disco king’ Penny Penny who has a popular reality TV series on South African television) it owes its popularity to pioneers such as Thomas Chauke. Born in 1952 in Saselamani Village, Limpopo, his professional music career started in 1980 with Gramophone Records.

Picture credit: https://www.afriquedusud-decouverte.com/

His style makes heavy use of electric guitar and he is often backed by female dancers. He is credited with aiding the evolution of Xitsonga music – in 2010 the University of Venda recognised him with an honorary doctorate (PhD) for his contribution to music.

Tsonga artists such as Sho Madjozi (Maya Wegerig) are merging their culture with modern sounds. The rapper is making waves in the South African music scene with her vernacular lyrics and a futuristic sound and aesthetic as seen in the below video: